Greenwashing could slow our progress towards meeting climate and social goals. Here's how policy-makers, organizations and consumers can spot it – and end it. Originally Published in World Economic Forum.

The adoption of the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy on 21st April – an investor's guide that defines green investments – has become embroiled in a greenwashing scandal. This taxonomy was intended to be the EU Commission’s keystone regulation underpinning the sustainable finance pillar of the EU Green Deal, with the objective of preventing greenwashing.

However, after intense lobbying the final regulation may permit gas, a fossil fuel, to be labelled as ‘green.’ This ignores the environmental effects of methane, which has a climate impact up to 84 times greater than CO2 in a 20-year timeframe and which leaks from natural gas production. If gas leaks only 3% of its methane content, it causes even more warming than coal.

Sadly, the taxonomy that was to be the standard to prevent greenwashing may itself become an enabler of greenwashing.

What is greenwashing and how common is it?

Greenwashing refers to 'green' or 'sustainable' practices or products, while ignoring their total contribution to climate change and or the Sustainable Development Goals such as biodiversity or environmental pollution. Greenwashing generally takes two main forms:

- Selective disclosure. This means advertising positive information regarding a product's environmental performance while hiding the negative. For example, some paper products claim to be ‘green’ based on a narrow set of attributes without attention to other important environmental issues. Paper, for example, is not necessarily environmentally preferable in aggregate just because it comes from a sustainably harvested forest. Other important environmental issues in the paper-making process, such as greenhouse gas emissions, or chlorine use in bleaching, may be equally important.

- Symbolic actions. These are claims that draw attention to minor issues without any accompanying meaningful action. For example, a bank may offset its own emissions while ignoring the climate impact of its investment portfolio. Or a fashion brand may donate to UNICEF while not addressing child labour in its supply chain.

Experts and NGOs have observed that greenwashing has become more common in recent years. As international awareness and regulations increasingly call for consumption and investments to be more sustainable, the potential for greenwashing also grows. The risk is that stakeholders switch their support to a less sustainable option, worsening the impact on both planet and society.

What can we do to stop greenwashing?

Some NGOs or media take the naming and blaming approach. This assumes that investors and companies that 'greenwash' are aware of what they are doing - but this is not always the case. Some may simply lack data. A CEO may have communicated a strong vision, but a strategy has not yet been fully integrated across all departments. Perhaps the necessary tools to deliver their strategy may not be available yet.

On the other side of the spectrum, we can identify and reward those investors and companies who set their ambitions high and in line with achieving globally agreed targets such as the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and then deliver real progress toward that ambition.

But how do we know when ambition is sufficient, and what progress has really been made? This requires common definitions and reporting standards built on growing scientific understanding of climate change, poverty, biodiversity, pollution and other societal measures, and credible ways to consistently measure impact.

How do we measure impact?

There are two common ways to assess the impact of a given product or organization.

- Inventory reporting: Measuring and reporting the impacts of an organization's operations – such as carbon emissions, biodiversity impacts, or social equality.

- Impact quantification: Measuring the impact of a particular effort or investment to compare what would have happened in its absence.

The financial community and companies under EU disclosure are accustomed to annual inventory reporting on environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance indicators. This helps paint an overall picture of alignment with climate and SDG targets at the macro level. However, it does not identify or reward the financial organizations, companies, or cities that contribute the most to achieving the SDGs and climate goals; nor is it effective at limiting greenwashing.

On the other hand, quantifying impacts against a baseline gives a clear measurement of the contributions of a wide range of climate efforts: individual projects, funds, or portfolios, and even cities’ urban plans.

The way forward

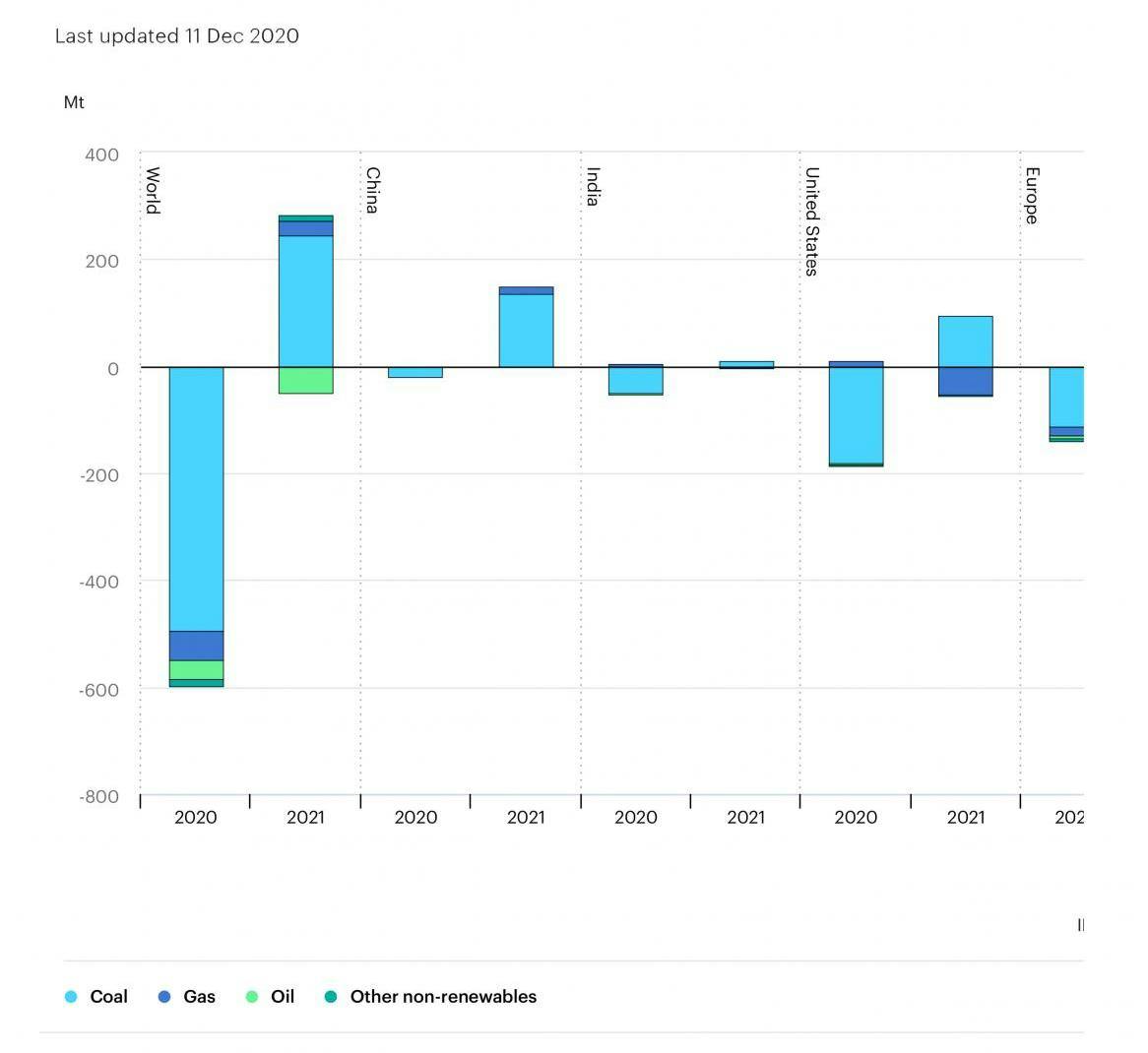

Projected global change in CO2 emissions, 2020 and 2021

IEA, Projected global change in CO2 emissions, 2020 and 2021, IEA, Paris

image: IEA Global Energy Outlook 2021 - Emissions are set to rise by the second-largest amount ever this year

The alarming evidence from recent scientific studies indicate we are not on track to meet our climate and social goals. Greenhouse gas emissions are predicted by the International Energy Agency to rise to the second highest level since records began, and we are way off track to achieve the SDGs. If not kept in check, greenwashing will further derail progress. We need to take bold action, now, that is robustly measured and transparently reported.

For this, we need credible inventory and impact standards. Used together, they can provide a serious approach for stemming greenwashing, while supporting those investors and companies who really do make a difference to stand out from the crowd.